This article was published on https://www.hcamag.com.

Technology continues to change our lives, including our working lives, at increasing pace. Automation, robotics and artificial intelligence have already significantly changed and will continue to change the nature of work – both the mix of tasks within existing jobs and the mix of jobs that will exist in future. Technology will also continue to change how and where we work, and how work is organised.

Will technology enable future workplaces where there is no gender or any other form of pay gap or inequity in employment? If technology is replacing women’s jobs, does dealing with gender equity in the workplace matter now?

One writer hypothesises that, assuming humans pre-empted the risks of developing smarter-than-human machines by ensuring some ethical basis to artificial intelligence, then that artificial intelligence

“would want to “smarten” its society by attempting to resolve the inequities that currently exist among humans…. We probably want to clean up our act before this happens – and we’ll be much happier if we do even if AI never appears.” (written in 2008!)

The flow on effects of technology’s impact on the nature and mix of jobs and on how we work will not necessarily affect gender equity negatively or positively. They could either promote or detract from gender equity depending on how we respond. Organisations can have a direct impact on this through how they respond to these challenges now.

The Covid-19 pandemic presented organisations with a number of challenges and has highlighted some issues, and provided some lessons, in relation to the future of work and gender equity. It spotlighted two of the contributors to the gender pay gap – occupational and vertical segregation – essentially the type of roles in which women are employed – with females employed in “essential worker” and frontline roles which are often lower paid. Women have been at the front-line of the pandemic (the health sector is 85% female in NZ) and most affected by job loss (complete or partial) with over two thirds of lost jobs being women’s jobs between March and September 2020.

The pandemic has also provided us with an example of how organisations can use technology to respond to the significant challenges presented by events such as the pandemic, and how this could work to both organisational and employee advantage to improve gender equity at work.

The impact of the changing workscape resulting from technology is uneven across sectors and occupations. While automation and robotics initially replaced many manufacturing jobs which were male dominated, women are as likely to be employed in jobs that now face the highest automation risks. A recent (2019) McKinsey report suggests that women may be slightly less at risk of losing their jobs due to automation, but women do make up a higher share of roles such as clerical support and services roles which are jobs that face significant job displacement due to automation. McKinsey also suggest that more women than men will face partial automation of their roles in future. Robotics and artificial intelligence appear set to affect female-dominated jobs further, with even some aspects of face-to-face caring roles potentially being replaced by robots.

The uneven impact is also seen in New Zealand. Recent analysis of the changing occupational mix in New Zealand found that the New Zealand workscape changes are broadly similar to the US or Australia and that there has been pronounced growth and change in the mix of occupations within the ‘community and personal services’ occupation group and within ‘clerical and administrative’ occupations.

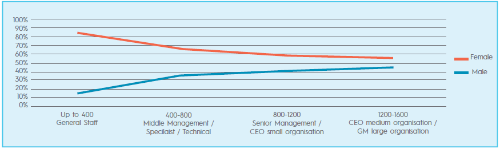

Recent analysis of our remuneration database highlights that a key contributor to the overall gender pay gap is occupational and vertical segregation – i.e. where and at what level women are employed. The McKinsey report identified that healthcare and accommodation stand out as sectors where women could make significant employment gains relative to men, so occupational segregation may not be such a hospital pass for women after all. However, our data also shows that in New Zealand, while women make up 85% of the healthcare workforce, they are clustered in roles at the lower end of the pay scales in this sector (see graph below).

So while females are currently employed in sectors where job growth is predicted, gender inequity will not reduce if women remain in the lower paid roles with the result that the ongoing growth in the healthcare sector could magnify the pay gap. Addressing inequity now remains as important as ever.

Technology is affecting both the nature and mix of jobs and also affecting how and where we work. Organisations have been forced to consider totally different ways of working to deal with the automation and now digitisation/computerisation of many work functions. Many manufacturing and clerical roles have been completely re-framed.

Organisations also had to consider different ways of working as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. During the lockdown phases of the pandemic many people were required to work from home and widespread adoption of technology allowed many more of us to do so than would have been the case in the past. Working remotely, rather than having to travel to workplaces enabled employees to balance work and home responsibilities. Lack of the “normal” childcare options, such as school or kindergarten, required parents to manage work and home responsibilities in a different way and required their employers to allow them to do so.

The lack of flexible working options is one of the contributing factors to the gender pay gap and employment inequity, because it means that many employees, particularly women who have traditionally been the carers, have had to make trade-offs between their career and their caring responsibilities. As a result of the pandemic, new flexible working practices, such as working remotely and the flexibility that allowed, became more prevalent and more accepted. Our Pulse surveys, run during and after the lockdown, found that 70% of employers fast tracked flexibility and remote working practices and 60% developed new people initiatives or ways of working. This development has the potential to contribute significantly to improving gender equity in the workplace as organisations normalise the practice and therefore the concept of flexible working.

While underlying societal attitudes contribute significantly to gender inequity in the workplace, the pandemic showed that an organisation’s actions can have an impact on inequity.

Bigger questions around how society will deal with the impact of technology, such as a lack of paid work arising from technological advances, are beyond any one organisation’s scope of impact. This will require government policy measures with proposed solutions such as a universal basic income. The pandemic also required governmental intervention to reduce the negative and often inequitable impact on individuals and the economy. However, it is still in organisations’ interests to continue addressing inequity themselves within their sphere of influence, because the choices that organisations make in response to technology will have a significant influence on how technology will affect equity in future workplaces.

Much of the focus for addressing inequity has been on closing the gender pay gap and organisations have been tasked with dealing with this in New Zealand as elsewhere around the world. Closing the gender pay gap today will not solve the problem in the future, and just addressing pay inequities will not resolve gender inequity at work – the causes run much deeper than that. Nevertheless, addressing pay inequities is a good place to start because it forces organisations to focus on the broader employment issues that result in a pay gap.

There are a number of broader human resources and employment practices that employers need to address if they really want to close the gender pay gap and address inequity in the longer term. A number of these measures will also assist with the transitions facing women in the workforce as technology affects the range and nature of jobs available:

- Remuneration: Ensuring that the pay levels for roles are related to the actual level of responsibility and skill required in the role, not what the market pays for similarly titled roles.

- Flexibility: Establishing a culture that enables flexibility regardless of status, including employment, marital, family, sexual orientation, age etc.

- Development: Ensuring that, regardless of part-time or full-time status, gender, ethnicity, age, all relevant development opportunities and reward options are available and accessible to all employees

- Mobility: Encouraging women into a broader range of occupations and to put themselves forward for development and promotion, to take full advantage of technology and the emerging occupations.

When and how the world emerges from the impact of the pandemic and which businesses will survive and in what form is still uncertain. As with the on-going impact of technology, organisations and employees will have to reinvent themselves, and how work evolves in the face of these challenges will have a significant impact on gender equity in the workplace.

As technology changes the face of work and the impact of the pandemic continues to affect how we work, organisations need to continue to address the issue of equity in employment and make sure that technology continues to contribute to equity rather than work against it.